Tomorrow marks one-hundred years since the start of the Scopes Monkey Trial in my hometown of Dayton, Tennessee. If you aren’t a history buff, you might not have heard of the trial…or maybe you vaguely remember studying it in American history class in high school. (Here’s a nice summary, in case you need a refresher). In short, the Monkey Trial was a show trial, meant to test the Tennessee law that said it was illegal to teach the theory of Evolution in public school. John T. Scopes was a substitute teacher who volunteered to be the defendant after town officials hatched a scheme to host the trial as a way of drumming up business for the economically floundering town.

These days, most folks only remember the trial when it comes up as a Jeopardy question. But it was a really big deal at the time, a culminating event in the rising tension between science and religion, between tradition and progressivism. It was the first trial to be covered by the mass media and broadcast live on the radio directly into kitchens and living rooms across America.

And while the topics in question have changed, what role the government should play in the education of our children is a perennial question, with the Supreme Court recently ruling to allow parents to opt out of public-school courses that use LGBTQ+ themed storybooks.

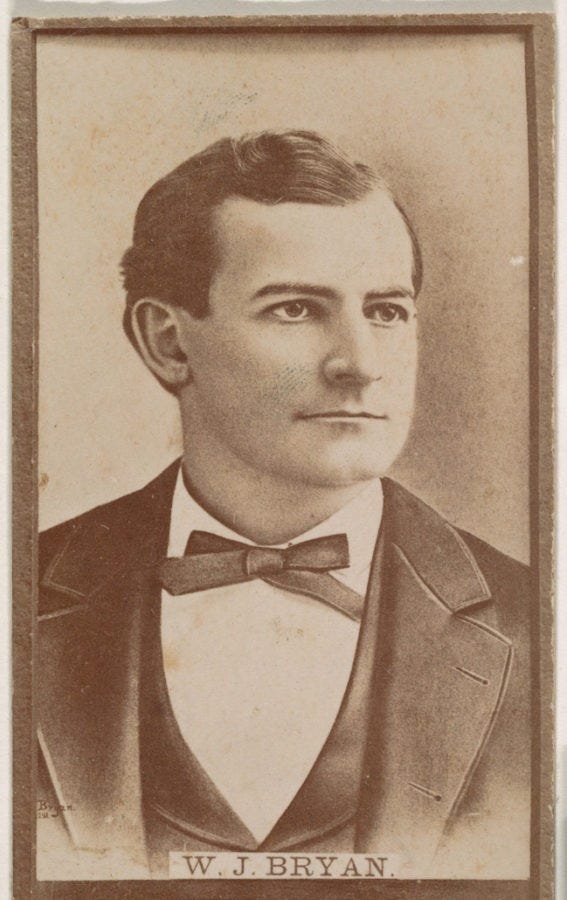

Growing up in Dayton, of course, the trial was always there, casting its long shadow on my childhood, my Christianity, and my perception of what it meant to defend the faith. William Jennings Bryan, the prosecuting attorney, is a large and looming figure in my imagination, as he was both a hero of my childhood faith and the namesake of the college I attended. Clarence Darrow, the defense attorney and outspoken agnostic, was the clear foe. Every July, our town would host a re-enactment of the trial in that old brick courthouse. My friends would play the role of testifying students, and my favorite professor was cast to play Bryan several years in a row. My best friend’s dad played Darrow. Food trucks and craft vendors would pop up on the downtown sidewalks during the re-enactment, and we wondered as we sweated out on that courthouse lawn if it was as hot as that famously hot July in 1925.

I recently wrote an article for Religion News Service about my changing relationship with the trial and my perception of the famed orator and three-time populist presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan. My own sister’s rise to prominence in the world of religious discourse began with a memoir she wrote (originally titled Evolving in Monkey Town) about growing up in the town that is often dubbed the home of modern fundamentalism.

Clearly if you grew up Evangelical in Dayton, Tennessee you have…

…feelings about the trial.

These feelings do indeed evolve, progressing in various phases. Phase one, at least for me, was marked by a deep sense of unreserved pride that your hometown defended the Bible from the aggressive attacks of secularism and atheism. Bryan is the unquestioned hero to be celebrated for his courage and tenacity. As a zealous young Evangelical, when people would ask me where I was from, I would proudly tell them I was from Dayton, and assume they knew that it was my people who took on godless ideology and didn’t flinch.

Phase two is when the questions begin. The wariness is silent at first, as misgivings about Bryan’s approach (and frankly, Darrow’s brilliance) begin to creep in. This phase is characterized by a growing sense of unease. You begin to wonder if it really was such a bad thing for evolution to be taught as a theory in biology class…that maybe kids in the 1920’s had a right to learn all sorts of perspectives just like you had. Meanwhile, Bryan’s ghost-like presence presides over your internal deliberation, yes as judge, but also as a sort of father-like faith figure.

Phase three is a smug (an often outspoken) indignation…at the fundamentalism embodied by Bryan, the movement he seemed to initiate, and perhaps Christianity itself. This phase often coincides with a deconstruction of faith, and a questioning of all the beliefs you formerly held as essential and an unseating of all your erstwhile heroes. In stage three, Darrow ascends to the role of hero as you realize Bryan – and all the religious fundamentalists in your hometown – were the butt of an inside joke that nearly the entire nation was somehow in on. If you’re in the throes of stage three and someone asks you where you a from (and that someone knows anything about religious history in America), you mumble your answer under your breath or change the subject.

Or at least, that’s how it went for me.

My journey was similar in many ways to my sister’s. But fifteen years after her memoir was published, I find myself somewhere past phase three and in what feels like something of a softening - a deeper curiosity perhaps. As fundamentalism and progressivism continue to dig in, and we face an increasingly divided and vitriolic media ecosystem, I’m feeling tender…and yearning for kindness more than ever before.

It was in this spirit of curiosity (and in honor of the hundred-year anniversary) that I began to research the trial, hoping to re-encounter it once more but this time as an open-minded adult who had also re-encountered my faith. I read articles, listened to podcast, and checked out a small stack of books about the trial from the Appalachian State Library

I spent a lot of time reading the atheist media pundit H.L. Mencken’s dispatches from the trial, dispatches that are collected in a book entitled A Religious Orgy in Tennessee: A Reporter’s Account of the Scopes Monkey Trial. I’d read snippets of Mencken’s reports before, so I expected to hear more critiques and perhaps some snide remarks about the religious residents of Dayton. What I did not expect was how vicious and dehumanizing his descriptions of Bryan and his southern “hillbilly” followers would be. I recounted some of Mencken’s vilest comments in my piece, so I won’t reiterate them all here. I also write there of the elements of Dayton’s story he left out (the boom and bust of the coal industry, the damage done at the turn of the century by the proliferation of the hillbilly stereotype).

I did not expect to feel Mencken’s words resonate so painfully in my body. I’ve never had to set a book down so many times to just breathe and compose myself. I made my way through his dispatches my mouth agape, and my heart racing.

I tried to pay attention to my body (as my counselor always urges me to do). And I can’t help but think that the tears and the tightness and the trembling I experienced while reading Mencken’s words had to do with all those formative years growing up in the shadow of the trial and the perceptions the outside world had of it. It is the internalization of all those stereotypes that were imposed on my community, the fear that somehow my faith made me a pariah, perhaps even a detriment to society.

But I also think reflection on the trial has brought back memories of all those “dark nights of the soul,” in which the faith of my youth was prosecuted by my own emerging doubts. It’s summoned those feelings of being suffocatingly pressed by an “either/or” mentality, the pressure to be for something or against it…an ethos in which the “in-between” does not exist.

I suppose phase four is when you realize that Bryan was not the buffoon Mencken (and phase-three Amanda) supposed him to be. Upon further study, you’ll learn that Bryan was a champion of women’s suffrage and public education. He vehemently opposed imperialism. He defended the working class, pushing for a minimum wage, an eight-hour workday, and the right of workers to unionize.

Like Bryan, I am beginning to see that religion brings more to the social and cultural table than skeptics care to admit. Bryan’s passionate opposition to Evolution seems not to have been motivated by fear of change or by ignorance. Rather, he was animated by a strong conviction that the theory of Evolution enabled the discrimination and dehumanization of eugenics and social Darwinism (the latter of which Mencken was a proponent). “The Darwinian theory,” Bryan wrote, “represents man as reaching his present perfection by the operation of the law of hate — the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill off the weak.” Bryan was committed to the Bible because in it, he saw a law of love that insisted on the just treatment of all.

Bryan’s conviction is complicated by the fact that he never adamantly opposed the Jim Crow laws espoused by members of his Democratic Party at the time. And Darrow, the supposed enemy of the faith, has been lauded at times as a champion of the Civil Rights movement for his brilliant defense of Ossian Sweet, a black man who was accused of murder after defending his family from a white mob.

I suppose my evolution of feelings around the trial has meant a greater willingness to make space for all this complexity. Perhaps there should never be “heroes” of the faith…only fellow journeyman fumbling their way through their own flaws. The truth is, nearly every religion, every worldview, and every ideology can be used to oppress and dehumanize. Bryan’s Christian fundamentalism has been misapplied and leveraged to justify all sorts of marginalization. The evolutionary theory was the permission slip racists and bigots needed to embrace eugenics and forced sterilization. All peoples (whether they be pagan, Christian, atheist, scientist, rich, poor, educated, or uneducated) are prone to oppress, to belittle, to exploit.

Which is why for me, an evolving faith means learning to never put your faith in a person. God alone is worthy of our adoration, our obedience. It means trusting that no one person can be the embodiment of all you believe, nor does their failure indicate a failure of the faith itself.

An evolving faith also means learning not to internalize stereotypes that are imposed on your faith and people who hold your religion. It means considering all the evidence, (and yes, perhaps the whispers of the Holy Spirit) and deciding for myself what I believe regardless of what I fear people will say about me. It means releasing my fear of being associated with Christians and Christianity. While Christians are certainly imperfect, they are rarely the caricatures that critics contend with on the internet.

Mencken did a disservice not only to rural Christians, but also to norms of discourse. As I wrote in my RNS piece, “Mencken’s coverage of the trial helped explain the legacy of mistrust for mass media among the rural and religious. But it also offers a vivid illustration of how prone we are to make our political and religious adversaries caricatures rather than contextualized characters with complicated stories, unique insights and real convictions.”

I am a Christian. I am from Appalachia. I’ve lived in small towns most of my life. I am learning to own all of that, to be proud of it, and to consider how I might contribute to the health and wholeness of my home and my community of faith, rather than fight against it. I learning to commit to being the best version of myself both because of and despite these spaces rather than to deny my identification with them.

Two statues now adorn the lawn of the Rhea County Courthouse. To the left, William Jennings Bryan stands upright in suit and bowtie, his face pensive, his hand resting on stack of firm stones, one of which is engraved with the words “truth and eloquence.” To the right is Clarence Darrow, pointing a crooked finger at some unknown figure in the distance, the thumb of his other hand hooked around his suspenders. His shoulders are bent, his scowling face is resolute.

However these figures may appear in your own imagination, I now feel nothing but pride…that these two giants of the early 20th century met in my hometown to have a really important conversation about faith and science and culture and civics. My faith is now better able to withstand that trial, in hopes that someday mutual understanding and deeper love will be the law of the land.

Thanks for this thoughtful piece. Trying to stop the caricature and stereotyping of those I trust and those I don't -- that's not easy work. But it sure is important!

As a New Englander, I discovered the trial from its fictional reimagining in the play Inherit the Wind. They made a TV movie version with Jack Lemon and George C Scott.

Also, your four stages of evolving beliefs is a great mirror to McLaren’s four stages of faith outlined in the great book Faith After Doubt.